Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXXIV No. 2, May 1-15, 2024

Shedding new light on Harischandra (1932) and Galava Maharishi (1932)

-- by S.A. Muthuvel, muthuvelsa@gmail.com, translated by Varsha V.

This article is an attempt to learn more about Harischandra and Galava Maharishi, the 100 per cent Tamil talkies that followed in the wake of Kalidas. The period of study is one in which there were no magazines dedicated to film; in fact, the print media of the time hardly accorded much importance to cinema, so it is challenging to unearth new evidence on our subject. The only credible – and therefore crucial – source available is an interview given by Sarvottam Badamito Theodore Baskaran.

Readers may feel that this documentation is hardly sufficient to discuss two historical films. However, a recent project to bring out an anthology of Tamil song books up until the 1940s has led this author to discover that these two productions – Harischandra and Galava Maharishi – are among those films for which no song book was printed. Given the state of affairs, the available evidence has rejuvenated an academic interest in these films. And so, this column will examine new revelations alongside what is already known, such as the well-known fact that the 1932 Raja Harischandra was the very first film to include a few colour scenes in its feature.

The Directors

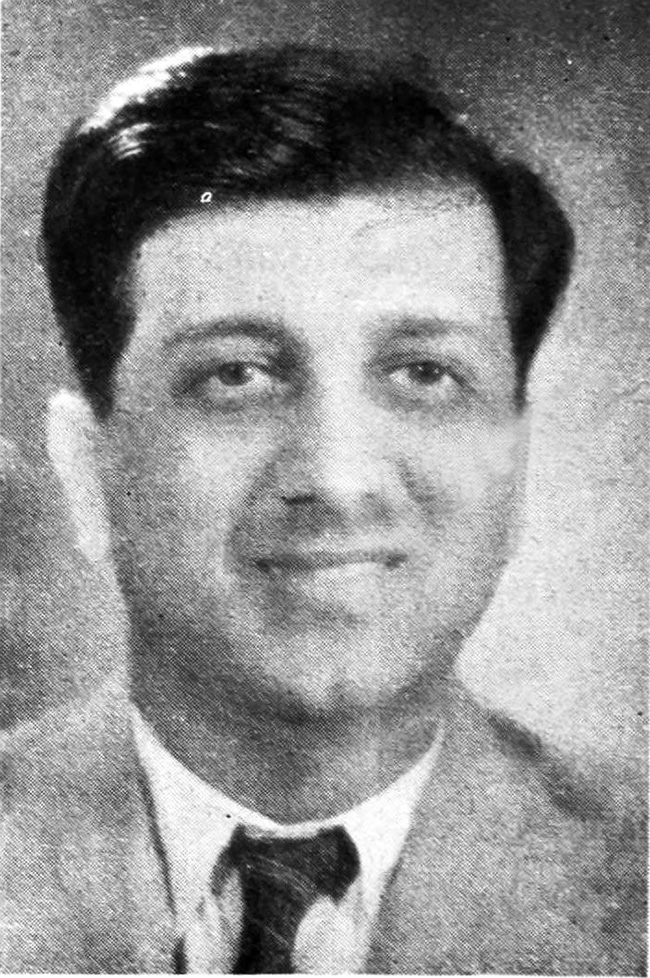

Sarvottam Badami.

Sarvottam Badami.First, we shall take a look at the directors of Harischandra and Galava Maharishi. The facts that have been established so far are as below:

Raja Harischandra: Sarvottam Badami, T.C. Vadivelu Naicker and Raja Chandrasekar.

Galava Maharishi: Sarvottam Badami, T.C. Vadivelu Naicker and P.B. Rangachari.

We shall now assess the truth behind these claims as well as the contribution of each of the named to the productions on the basis of newly obtained evidence.

First though, a brief background of the times. Since the technique of film-making was then imported from foreign countries, it was largely foreigners who had been trained in the art and could work as film-makers. Indians who had travelled overseas and had been similarly trained as well as those who had acquired the requisite skills on home soil focused their energies on making silent films. A few key names in this regard are R. Nataraja Mudaliyar, R. Prakash, A. Narayanan, Raja Sandow and R. Padmanabhan. Talkies produced in Indian languages were a little late in the coming. It was during the reigning silent film era that the first Hindi talkie Alam Ara was produced in Bombay and released in 1931. To produce Tamil talkies, people had to travel to Calcutta, Bombay, Kolhapur, Poona etc. until as late as 1934, the year when A. Narayanan established the very first sound recording studio in Chennai.

T.C. Vadivelu Naicker.

T.C. Vadivelu Naicker.Coming back to Harischandra and Galava Maharishi, we have already noted that they were released within a few months of Kalidas. They were filmed one after the other at Sagar Movietone studio in famous Chowpatty, a seafront in Bombay. Both movies were pure Tamil talkies, through and through. However, the honour of being the world’s very first 100 per cent Tamil talkie goes to Raja Harischandra. Apart from being produced in the same studio, the films also shared a film crew hailing from Tamil Nadu. The crew worked under the leadership of T.C. Vadivelu Naicker and advocate Sundara Rajan. T.C. Vaidvelu Naicker was a dynamic personality; as a member of the Suguna Vilasa Sabha, he worked as an actor, theatre director and writer all at once.

The crew themselves consisted of artistes from the company as well as amateurs. Both films saw V.S. Sundaresa Iyer from Varkalai and D.R. Muthulakshmi from Dindigul play the roles of the hero and heroine respectively.

It was a director who had been trained at Germany who first began to work on Harischandra at Sagar Movietone. However, issues arose between the gentleman and the Tamil producer, due to which the German director could not complete the film. Thus, the movie was half done when the responsibility devolved on Sarvottam Badami who was not only South Indian but also a professional who had been trained in sound recording. Badami was around 20 years old at that time. He had actually begun his career in Bangalore at Ambalal Patel’s firm Maharaja Cycle & Motor Co and later shifted to Bombay as his employer had wished him to get a grip on the motor business.

It was there that he met Ardeshir Irani and Chimanlal Desai, leading to his employment at Sagar Movietone. By Badami’s own admission, he had no experience in film direction at the time he was given the responsibility to complete Harischandra. The film had already made substantial progress by the time it came to him; Badami’s key contribution, quite evidently, is that he added sound to the silent film, while also managing to wrap up the direction largely by trial and error. It was T.C. Vadivelu Naicker who made up for the rest of the work. Paraphrasing Badami’s own words from his interview to Theodore Baskaran, he merely re-heated and served a meal that had already been cooked.

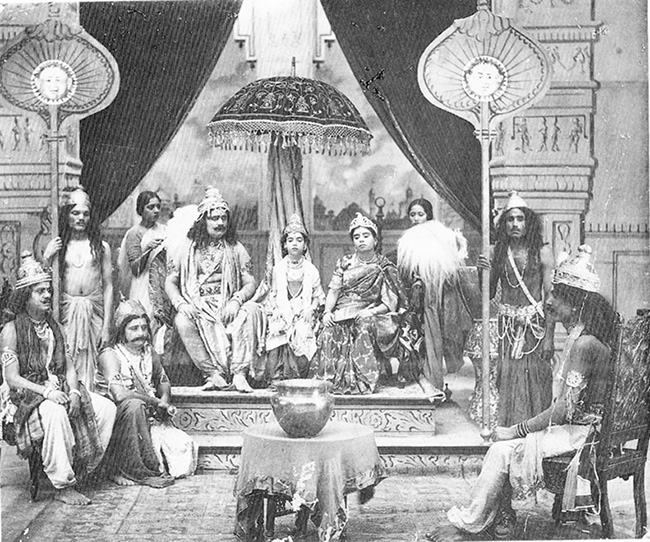

A still from Raja Harischandra.

Films are made when art and technology come together. The person who works on the portions relating to art is dubbed the playwright while the person who works on the technological aspects is dubbed the technical director. It is a matter of note that this distinction came into being in Tamil cinema after the release of Harischandra and Galava Maharishi, where T.C. Vadivelu Naicker served as the playwright and Badami the technical director.

Despite this variance, it was the person who worked on a film’s artistic presentation who was acknowledged as the director. A few examples, below:

Prahlada (1933) was the third movie directed by Vadivelu Naicker. However, the credit for the film’s technical direction is documented to the name Kali Prasad Ghosh. Sarvottam Badami’s contributions to Harischandra and Galava Maharishi were much in the same vein.

Pammal Sambanda Mudaliar, while writing about his experiences directing talkies, clearly specifies that the technical director of Sati Sulochana was the German Bulli. But the film’s song books and other records credit Sambanda Mudaliar’s name as a director, too. (Readers may note that a peculiarity of the period was that some films did not mention the director’s name at all in song books and other promotional material.)

A cinema publication brought out in 1936 carried a feature on Tamil movie directors, in which the writer is seen taking a light, rather indulgent tone on the subject, as though the role was rather inconsequential in film-making. The article writes about Vadivelu Naicker thus: Shriman T.C. Vadivelu Naicker: He is not a graduate. Even so, he has good experience with the stage. He is a well-read scholar in the Tamil language as well as in classical music. Until now, he has been the playwright for three films, and the director for four. Vel Pictures’ Pattinathar that he directed has met with a good measure of success.

The film posters and advertisements for Raja Harischandra make mention of its crew in the following manner: Directed by S.R. Badami, under the personal supervision of T.C. Vadivelu Naicker, member of the Suguna Vilasa Sabha, Madras.

The above are evidentiary documentation gathered by this author. Some latter-day records specify Badami’s name as Sarvottam Badami as well as S.L. Badami.

Until now, the name Raja Chandrasekar has been specified – albeit with much uncertainty – as one among the directors of Raja Harischandra. Recently procured records do not mention this name at all. So, it is quite certain that T.C. Vadivelu Naicker served as the stage director and Sarvottam Badami served as the technical director for both Harischandra and Galava Maharishi. No one can contest this claim.

Overseas dailies of the period carried advertisements for Galava Maharishi too, but the director’s name is missing from these records. The ad runs thus: A portion taken from the epic Mahabharatha, adapted for the stage by Pammal Sambanda Mudaliar, and filmed per the drama script. (Curiously, T.C. Vadivelu Naicker’s name is absent from most of the films he worked on. For instance, he directed both Pattinathar and Kavirathna Kalidas, but the song books and promotions do not mention the director at all. There are other examples, too. Perhaps he avoided such credit wishing to shun publicity.)

Official Movie titles

The first 100 per cent Tamil talkie released in 1932 has been referred to variously as Harischandra, Sampoorna Harischandra and so on. The title of the film is actually Raja Harischandra. It was dubbed Harischandra for short.

Even before this production, the title Harischandra had been used for films both silent and talkie in Tamil and other languages. In those times, Sanskrit had a strong influence on Tamil; the names of Tamil plays and films were hardly ever in chaste Tamil. Even Galava Maharishi has many monikers such as Kalava, Galwa, Kalavarishi and the like; the official titles of the film are Galava Maharishi and Chitrasena Upakhyana (it was a custom of the period to accord two titles to a film).

Which came first?

There are differing opinions about which film came first, Harischandra or Galava Maharishi. But the evidence is quite clear on this point.

1. The interview given by Sarvottam Badami to Theodore Baskaran has the former going on record that it was Harischandra that was the first to be released. Other evidence procured by this author attest to this fact. Harischandra was released at Kinema Central Theatre in Chennai on April 9, 1932. It ran for four weeks, after which it was taken directly from Madras to foreign shores and screened abroad.

2. The Censor Board’s documentation also confirms that Harischandra was released first. Both Harischandra and Galava Maharishi were made in Bombay and received their censor certificates there. Harischandra was screened to the Censor Board on April 4, 1932; it was awarded the censor certificate the same day, the document number being 11213. Galava Maharishi was screened to the Censor Board on May 31, 1932; it was also awarded the censor certificate on the same day, the document number being 11356.

3. Galava Maharishi’s own advertisements claim that the film was ‘produced in a much more spectacular fashion than Harischandra.’ There is no doubt that Harischandra was the first on scene between the two films.

The first colour film

Harischandra was advertised as the ‘first Tamil talkie with technicolor sequences’. It is a point of note that black and white films were being produced up until as late as 1970; so, it is perhaps understandable readers may feel surprised that a 1932 film – the first truly Tamil talkie, no less – presented colour scenes in its feature.

Many may have heard of Gevacolour, Eastman Colour and the like. These are all names of various technologies relating to colour films. There are many others too. One such technology is Technicolor. In fact, colour sequences had been proved possible in films predating 1932, as part of silent films. However, the reader must take into account that colour film technology, like other sciences, has also evolved over the years. The early features cannot be imagined on par with the colour films we enjoy today.

At the very basic level, colour films need three colours – red, green and blue. Until 1932, only red and green were in use in colour film-making. Technicolor itself had only these two shades until Raja Harischandra was taken in 1932. Further, the available evidence makes it clear that the entire feature was not in colour – only some Tamil sequences were, such as a couple of songs in the beginning of the film and a few other scenes.

As for Galava Maharishi, there is no evidence that the feature included colour sequences.

Advertisements

In his book Pesum Pada Abubhavangal (Experiences with Talkies), Pammal Sambanda Mudaliar writes the following:

Of my plays, the very first one to be produced as a talkie was Galavarishi. My friend T.C. Vadivelu Naicker requested my permission to adapt it as a talkie a few years back and travelled to Bombay to produce the film. When I saw the movie in Chennai, the excellent performance of the character of Subhadra filled my heart with satisfaction.

Pammal Sambanda Mudaliar participated in the release function of Galava Maharishi too.

Critics

Sundaresa Iyer’s voice in Harischandra was very sweet in speech and song. So too was Muthulakshmi’s in the tunes she rendered. The sound recording suffered a shortfall when she sang at high pitches – in fact there were similar issues here and there in other places in the film – but overall, the sound recording had been done quite well for the film.

It appears that the film tents saw an outpouring of crowds for both Galava Maharishi and Harischandra. Badami says that people watched the talkies with great amazement. In those days, a film’s capital was recouped if it ran but for a few days; that Harischandra ran for four weeks in a single theatre was a stupendous achievement. Keep in mind that a film of this period had not more than 4 copies of the production; so, it stands to reason that Harischandra must have had to be taken to towns one after another to cover the whole province. In fact, a copy must have eventually been taken overseas too. The claim that the movie ‘ran for a year’ was made taking into account only its shows in the province. As a benchmark stat, consider this – later in 1936, the very same T.C. Vadivelu Naicker would go on to direct Pattinathar which would break all known records and run for a mammoth 14 weeks in a single theatre in Madras.

The screenings of both Harischandra and Galava Maharishi were accompanied by the distribution of 12-page song books which not only contained synopses of the stories but also stills from the films, a list of the artists and song lyrics. This much is evident from the available documentation. However, there is no record of anyone getting their hands on a sample of this material.

Interestingly, recently obtained documents such as issues of The Hindu and Sound and Shadow from that period mention only T.C. Vadivelu Naicker’s contribution to both films.

Raja Harischandra 1932

In general, many share stills from the silent movie Harischandra and other similarly titled non-Tamil talkies misattributing it to the 1932 Raja Harischandra. However, it is certain that the image presented here is a still from the movie in question – D.R. Muthulakshmi’s face is seen quite clearly, attesting to this fact. The same can be further confirmed by comparing the image with stills carried in overseas publications. On that basis, Sundaresa Iyer and Master Azhagunathan can also be identified. (It is to be noted that this particular photograph of V.S. Sundaresa Iyer is often misidentified as Raja Sandow.)

Actor V.S. Sundaresa Iyer – well-known for his performance on South Indian stages – played the role of Harischandra. D.R. Muthulakshmi of Columbia Records fame essayed the role of Chandramathi while Master Azhagunathan played the role Rohitashva. Also acting in the film were Parasurama Pillai, P.B. Rangachari, Raju Mudaliyar, M.V. Raju, Miss S.S. Janaki, Miss N.S. Ratnambal, V.M. Periyasamy Mudaliar, Subbarayulu, and K.K. Chinnaswamy Chetty. Fardoon Irani provided cinematography. As we’ve already noted, Sarvottam Badami worked on the sound recording and also received credit as a director alongside T.C. Vadivelu Naicker.

The film was 11,812 feet long and entertained the audience with a mammoth 39 songs, 25 of which were sung by D.R. Muthulakshmi and 8, V.S. Sundaresa Iyer. The Bombay censor certificate number was 11213 and 4 copies of the film were made.

Galava Maharishi 1932

On his 60th birthday that he celebrated in 1966, P.B. Rangachari said, “T.C. Vadivelu Naicker, who then worked at Sagar Film Company in Chowpatty, Bombay – the first Tamil director, in fact – made me act in Galavarishi and Harischandra. I am proud to say on this special day that I acted in the film Galavarishi, among the very first to have wholly Tamil dialogues.” (Source: Aarambha Kala Thamizh Cinema #1 by Aranthai Narayanan, brought out by Vijaya Publications.)

The propriety of including Rangachari’s name as director for Galava Maharishi can be assessed from the above statement. P.B. Rangachari was a trained bhagavathar and amateur drama artiste. He went on to have a long career as an actor in films but did not direct any movie. It was Badami and Vadivelu Naicker who directed both these films; they would go on to independently direct other films, too.

A brief synopsis of Galava Maharishi: While soaring through the skies upon a flying carpet with Urvashi, the Gandharva Chitrasenan spits out the juice of betel leaves. The spittle falls upon Galavarishi, who is at the moment engaged in meditation with his disciples. The rishi understands what has happened through his spiritual sight and curses the Gandharva. This incident grows to be the root cause of a fight between Krishna and Arjuna. (Source: Enathu Nataka Vazhkai by T.K. Shanmugam.)

T.C.Vadivelu Naicker – who started off as a member in Suguna Vilasa Sabha and worked as actor, writer and all-rounder in the drama productions of the father of theatre Pammal Sambanda Mudaliar’s troupe – received ample recognition for his work on Galava Maharishi. In his book Nadaga Medai Ninaivugal, he writes that he developed the Galavarishi play to the extent that people said, “The drama Galava is through and through a Vadivelu experience.” It can be surmised that Vadivelu Naicker chose to adapt Galavarishi into a film production among the 90+ dramas in Pammal Sambanda Mudaliar’s catalogue, as it had the greatest number of songs.

The film was shot at Sagar Movietone at Bombay over approximately two weeks. V.S. Sundaresa Iyer played the role of Chitrasenan while S.S. Janaki essayed the role of Urvashi (not confirmed) and P.B .Rangachari, that of Naradar. D.R. Muthulakshmi also acted in the movie. Some other characters in the film include Arjuna, Indran, Krishna, Mandu, Kamandu, Subhadra, Santhiyavali and Ratnavali. Faredoon Irani provided the cinematography and Sarvottam Badami, the sound recording. The directors were Sarvottam Badami and T.C. Vadivelu Naicker.

The film was 11,421 feet long, had 28 songs and four copies were made. The Bombay censor certificate number is 11,356.

A few evidentiary sources that were of help for this article:

– Theodore Baskaran’s interview with Sarvottam Badami as carried in The Hindu dated 20.7.1990.

– Experiences of a bureaucrat’s wife by Gita Vittal.

– Towards new genealogies for the Histories of Bombay Cinema: The career of Sagar Film Company (1929-1940) by Virchand Dharamsey.

– An interview given by Savottam Badami to AIR Bangalore on 11.2.2000.

– Documents from the National Film Archive of India.