Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVII No. 12, October 1-15, 2017

Glamorous go-getter from Chennai

by Janaki Venkataraman

Padma Lakshmi.

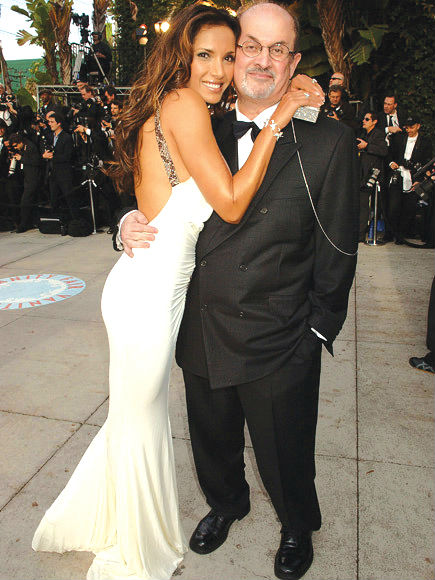

What happens to a middle class Tamil Brahmin, Besant Nagar girl, who has the longest legs in the neighbourhood and a fondness for thayir saadham and pickle, when she ups and follows her mother to the U S of A? Years later, she becomes the face of one of the most watched, Emmy award winning American cook shows, Top Chef (and gets to wear fabulous clothes and jewellery). Along the way, she also becomes a top model, occasional actor, cook book writer, columnist and arm candy (later, wife) of author Salman Rushdie. Padma Lakshmi is the prototype goddess of the Indian immigrant success story in America. (In Chennai we first came to know of her only when she brought Salman over to meet her grandparents.)

In her fast paced, very readable autobiography*, Love, Loss and What we Ate Padma traces her life from the secure roots in her maternal grandfather’s family in Besant Nagar, Chennai, (she went to school in St. Michael’s, Adyar) to her following her divorced mother who had left for America to build a life for the two of them. We see her coping with the excitement of her new life, the uncertainties of her identity as a brown skinned immigrant, her discomfort regarding her mother’s successive boyfriends, her early attempts to enter the world of modelling, her leaving after college to Italy, to pursue a career in fashion modelling. After initial struggles, she achieves what she set out to do, become a top European model, whose horizons widen as speedily as her Tambram inhibitions disappear.

Padma and Salman Rushdie on their wedding day.

A strict vegetarian to begin with, Padma began to eat meat in America, encouraged by her mother, who felt it was better nutrition. But it was during her time in Europe that she became a true foodie. Until then her favourite foods were spicy South Indian, with the occasional chaat thrown in. Europe opened the doors of fine Western cuisine to her, and the cheesemongers of Paris taught her to appreciate every kind of cheese there was. Then there was really no stopping Padma’s palate. It was inquisitive, adventurous and would try anything edible, at least once, from flowers to live snails. The recipes that intersperse the chapters in Love, Loss and What We Ate by Padma Lakshmi, Harper Collins India, are deceptive in their simplicity: thayir saadham, khichdi, chatpati chutney, egg in a hole etc. Padma’s culinary tastes are far more complex and informed. She offers an interesting recipe for a stomach cleanser, though, called Cranberry Drano. It is said to cleanse your insides after binge eating, as Padma is forced to do during shootings of ‘Top Chef’.

As for her love life, most of the men she has been involved with seem to be much older, wealthier and knowledgeable than her. That, of course, leads both the reader and the author herself to wonder whether she was not looking for father figures who could mentor and protect her, as her own father was always absent from her life. As a young model, she learnt from her much older Italian lover all about fine living; from Salman Rushdie, she learnt how to express herself in words (one cook-book, and several columns on fashion and food happened during this period in her life); from the billionaire lover she acquired after divorce from Salman, she learnt, well, how to live the good life; and from the youngest lover of them all, the only non-celebrity, she got her child.

There is a lot in the book about Endometriosis, a uterine condition that Padma suffered from most of her life until an enlightened doctor in New York treated her for it. (She blames the illness in part for the break-up of her marriage with Rushdie, as she was too ill to please him and he was too uncaring to understand her condition). Padma is currently co-founder of the Endometriosis Foundation of America that promotes early diagnosis and treatment of this painful condition.

The picture that emerges of Padma Lakshmi at the end of this book is that of a glamorous, globally successful, gently aggressive, go-getter of a woman. Yet there is a sub-text that portrays a woman who at heart still remains that wide-eyed, eternally curious girl who lived by the beach in Chennai and loved her Thatha and all her aunts and uncles and cousins and the jars of mouth-watering pickles her beloved grandmother made.

*Love, Loss and What we Ate by Padma Lakshmi (Harper Collins).

Excerpts

My grandmother emerged with a small katori, or bowl, with mashed-up lentils and rice from the kitchen. Her hand, wrinkled and worn, had mixed rice for every child of our family in this house for over thirty-five years. It was the same hand that had braided and oiled my hair, drawn countless marks of vermilion on my forehead, and had even landed hard on the side of my thigh when needed. This hand had shown Neela how to pleat her sari, and Bhanu the right way to burp Rajni and Rohit. It was the same hand that mixed batches of our secret house recipe for sambar curry powder twice a year, wielded the ladle of dosa batter when I first learned to make the fluffy thin crepes on the iron griddle, and administered Tiger Balm to KCK’s temples in the days when his head ached from the monsoon heat.

For a moment, I thought she might be the one to feed Krishna herself. I was keeping a low profile, doing as I was told. After handing me the bowl, she bent over, with agility, impossibly low, and applied a line of holy vibhuti ash across Krishna’s forehead as she lay writhing in annoyance. “Ippo, nee punnu,” Rajima said. “Now you do it.” Then I heard my mother’s voice, coming from a table where an open laptop was perched. She was tuning in via Skype and commanding me from Los Angeles. “Come on, Pads, the baby’s hungry!” I snapped to attention and placed a small espresso spoon of kichidi into the baby’s mouth. At first she coughed and sputtered, but in mere seconds, she seemed to be mashing the pap with her tongue against the roof of her mouth like an old toothless man. Everyone in the room seemed to exhale at once. I heard the hearty belly laughs of the priests.

I thought then that for the first time in my life, in that house, these women were finally saying: “Okay, you’re up. It’s your turn.” For the first time, I did not feel like a minor, a junior, or a half pint. For the women in my family, I had finally made it to full adulthood, into their club, the big league. For a second I mourned not only the final extinguishing of my girlhood…

Excerpts

The city of Chennai itself, however, was much different from what it was when I had built sand temples in the courtyard. The city that had felt in many ways like a sleepy town had become a frenetic metropolis. Much of the sand was now asphalt. St. Michael’s Academy had expanded into a large compound with tall buildings and fields for soccer and cricket. The Milk Bar that was once a leafy oasis was now a seedy, dilapidated place to be avoided.

Neela and I visited the old flat. All around our old building, urban development now made the area feel very congested. We could no longer see the ocean from my grandfather’s bedroom window. Taller buildings had been erected all around. Everyone wanted to live near the sea. The courtyard below had been asphalted, too. Children no longer made temples in the sand. I couldn’t believe how small the flat looked. It had always felt huge to me. I visited each room, could still see the lizards where the cracked walls met the ceiling. The place was empty save for some sewing machines and tailors, employees of Neela’s business. So many of us had grown up here, fought as children here, cried as teenagers, and often run back to this place as adults. Several sewing machines hummed as I walked barefoot on the old green marble from room to room. Underneath the hum, I could still hear echoes of Rajni tattling on me to Bhanu, the screech of my grandfather’s metal desk chair as he rose to say good-bye to a student. The house had never been beautiful, but it was beautiful to me, even in its dilapidated and empty state.

Yet for all the changes, much felt the same in the new apartment. There were still buckets of hot water for bathing, in spite of showerheads being installed in these new bathrooms. There were still far too many of us, old and young, from my grandmother to Krishna. We would crowd onto the floor, draping ourselves on pillows, grooming and feeding like a troop of monkeys, me scratching my nephew Sidhanth’s back, Neela braiding my hair, kids climbing among our bodies. Aunt Bhanu kneeling on the floor, peeling potatoes or mangoes. My grandmother haggling with every vendor she came across on the porch below.

And we still talked, a lot. Our conversations were a blur of languages. Everyone in the household was tri- or even quadrilingual. I grew up speaking Tamil, the language of my ethnicity; Hindi, the national language but also the language of Delhi; and English. Others in my family added Malayalam, the language of Kerala, my ancestral home, to that list. “Please” and “okay” were in English and bookended many bursts of speech.

“Please”- someone might begin, then switch to Hindi – “could you make some chai for me?” Then, without skipping a beat, she might continue in Tamil, “I’m really craving it” – then back to English – “Okay?” Certain words were just better in one language than another.