Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVII No. 15, November 16-30, 2017

Lost landmarks of Chennai

SRIRAM V

Discovering the Tinnevelly Settlement

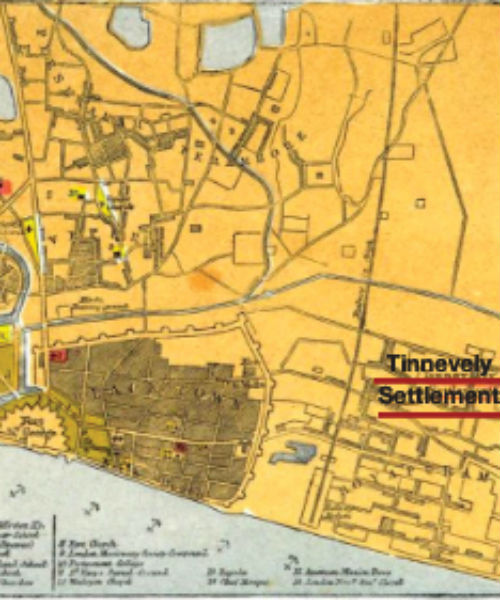

The red lines locate the Tinnevelly Settlement with reference to Fort St. George

(bottom left corner)

I have for long been intrigued by this name. What connection did Tinnevelly (present day Tirunelveli District) have with Madras city other than the fact that it was the southern extreme of the vast Presidency that our metropolis once lorded over? And yet, the Tinnevelly Settlement is a name that repeatedly cropped up in the 19th Century Municipal Administration records of Madras. It was a slum. To put it more correctly, it was a paracheri as the Government of the time usually designated such places. Clearly it was a spot where the most depressed classes lived and so the administration preferred to forget about it except on occasions when problems there began to have larger civic repercussions. The Church, for precisely the same reasons, interested itself in the place; its economic backwardness meant rich pickings for conversions. Thus, this brief account of the Tinnevelly Settlement is put together from Corporation and Church records.

Locating the settlement itself in today’s Chennai is impossible as the name vanished as early as the 1900s. But The Church Missionary Atlas of 1862 helpfully provides a map and in it the Settlement is clearly marked, being to the west of Royapuram. In today’s terms, it would therefore be where Old Washermenpet is. It is also from Mission records that we read of the first mention of this locality. On March 8, 1848, the Rev Bilderbeck of the American-sponsored Protestant Episcopal Church paid a visit there in connection with the conversion of a native. The locals protested and he had to go to ensure peace.

The Atlas referred to earlier gives us some further details. It states that the locality got its name from the fact that migrants from the southern district of Tinnevelly had made it their home a “few years back” and also notes that there had been a marked decrease in numbers in the immediate past years. That in effect is the only history we have. But given that Old Washermenpet was to become a heartland for Nadars moving into the city in the early 20th Century, it could well be that this area chiefly comprised members of that community, Tirunelveli being their heartland. The fact that it was also Christian dominated buttresses this assumption, for a significant percentage of Nadars had embraced that religion long before people like Bishop Caldwell made their appearance in South India and became active in Tirunelveli. The same Atlas also notes that there existed a Church and native school for converts in the Tinnevelly Settlement, the latter having 18 students in 1880. The chief profession of the local populace was rope making (a Rope Godown Street still exists in Old Washermenpet) and rice pounding – both of which were almost exclusive preserves of the Nadars before many of them became wealthy in the retail trade, setting up provision stores, and printing.

By the 1880s, the Church appears to have lost interest in the Tinnevelly Settlement. But the Municipal Corporation began to be concerned with it even from the 1860s. The Administration report of 1864 notes of efforts being made to open up this “block of huts”, the dense packing of which had made scavenging impossible, thereby causing an outbreak of cholera. But by 1873 the colony was evidently back to its old ways for the famed W.E. Dhanakoti Raju, afterwards Municipal Commissioner but then in charge of the Madras Medical Mission Dispensary, Royapuram, was to dwell on its condition at length. Three-fourths of the cases of fever in the past one year referred to him, he noted, were from the “village known as the Tinnevelly Settlement.” The poorest of the poor lived there, he wrote, and the walls were invariably damp. There were many swamps in the immediate vicinity and the rainy season saw the outbreak of cholera, which repeatedly claimed many lives. “The sanitary condition of the Tinnevelly Settlement,” he wrote, “deserves the serious attention of the proper authorities, and indicates forcibly the urgent necessity of sanitary improvements.”

It is not clear if that appeal had any effect, for in 1881 the report of Surgeon Major MC Furnell, then Sanitary Commissioner of Madras, echoed much of what Dhanakoti Raju had written. The President of the Corporation was then Sir Arundel Tag Arundel and he was moved to act. Noting that Furnell’s report was in no way an exaggeration, he stated that many attempts had been made in the past to improve the “loathsome place” but to no avail. That year, the Corporation allotted a sum of Rs 1,500 for improvements. The residents were moved to a temporary settlement elsewhere, the huts torn down, the streets widened and new residences built. Once the people moved back, they were expected to keep the area clean, free of encroachments and make improvements by themselves.

What happened thereafter is a mystery for there is no further mention of the Tinnevelly Settlement. It is quite likely that prosperity brought in a new class of settlers. Certainly it is on record that the new wave of Nadars who came in the early 1900s to Madras and stationed themselves at Old Washermenpet were well-off traders. The Settlement must have been subsumed by a housing colony.

Would like some information on Dhanakoti Raju

I am an NRI born and living in Canada and I have some information regarding Dr. Dhanakoti Raju.

Dr. William Edward Dhanakoti Raju was my great-great grandfather, and the first Indian graduate of the Madras College of Medicine (class of 1867). He and his friend Krishna Pillai were among the early Tamil converts to Christianity (Anglican). He was involved in the industrial business founding several foundries as well as in rural medicine (he is mentioned by Florence Nightingale on her book on Indian medicine). He wrote two books: The Elements of Hygiene and Queen Victoria: Her Life and Times. In the late 1800s he became a Municipal Health Commissioner for the city of Madras. His company Victoria Works in Santhomé cantonment was passed onto his eldest son David (his younger son Samuel is my great-grandfather). This part of Madras has been abandoned. He and his sons were all baptized and confirmed in St. George’s Cathedral.

His descendants married into many other prominent Indian Christian families.

This is all the information I have about him and if anyone has any more information please contact me as well.