Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVII No. 15, November 16-30, 2017

Madras – A Centre of Culture

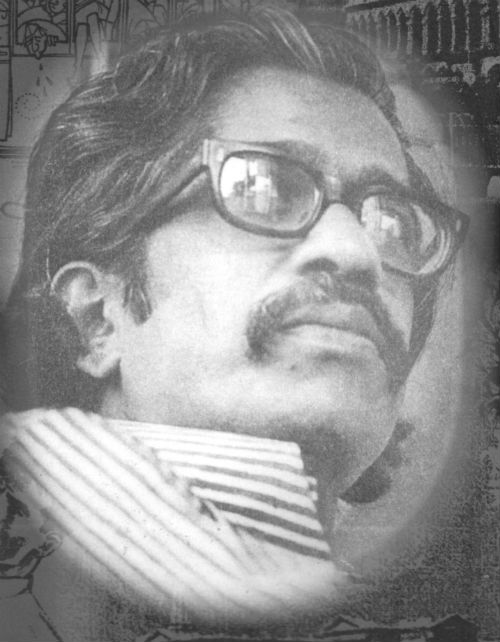

K.P. Balaji (1926-76) died in an air crash in Bombay. From Kathakali in Kerala, he moved to Marg, that cultural journal in Bombay. JoiningThe Illustrated Weekly of India, he was with it from 1954 to 1961. He then got into advertising with S.H. Benson’s and rose to be one of its Directors.His son, K.P. Karunakaran, settled in Australia, put together a collection of his writings and published them as a commemoration of his father’s 40th death anniversary. Over the next few issues, we publish a few of Balaji’s Madras-focused articles that appeared in The Illustrated Weekly in 1964-65.

TODAY’S ARTICLE IS A CURTAIN-RAISER FOR

THE MUSIC SEASON.

The Madrasi is often portrayed by his detractors as a timid and unsociable introvert who, for all his abilities, is so unambitious as to be unaffected by activities of the Joneses. This assessment is perhaps not altogether inaccurate, because, if anything, the Madrasi is most eminently qualified to mind his own business. And the fact that he does it rather well, most of the time with considerable profit to himself, is what, I suspect irks the Joneses most and makes the word “Madrasi” something less than a term of endearment outside the State.

In the field of culture, particularly, the Madrasi is quite smugly conscious that he is no less well (and perhaps better) off than anybody else, and he is inclined to make the best of it. The cultural season which was briefly but brightly here to coincide with the winter months, very much illustrated the point. If one was duly overwhelmed by the excellence of fare offered, one was equally impressed by the extremely efficient and business-like manner in which many cultural organisations function in the city.

If you have spent some time in Madras and have attended a few functions, the reason for this becomes quite obvious. Talk of Bharata Natyam or Karnatak music, and the voice of the true Madrasi hitherto strident about the anti-Hindi agitation or the rising cost of living, immediately assumes a tone of reverence and humility. He knows that, from here on, he is treading sacred ground. He can, of course, be as argumentative or dogmatic about the merits of one artist or another, but he wisely places the border topic of Art well above such petty squabbles. He has, I think, an instinctive grasp of what critics call the “basic values”. He can be parochial in his views, but his respect for tradition is genuine, and he is generally much better informed than his counterparts elsewhere about the nature and significance of his cultural heritage.

These qualities make him a good man to have in the audience – but he can be even better when you happen to find him on a committee. His loyalty to the arts never being in question, his native talent for hard and intelligent work makes him an ideal office-bearer. And he is remarkably free of some common failings you find in organisers of cultural functions. In the auditorium, he does not vie with the artiste to catch the public eye and – this is a very healthy sign for cultural organisations- he can keep the front rows tolerably clear of relatives.

There are bound to be exceptions. I am sure someone will point out at this stage that in Madras, as elsewhere, faction fights and personal jealousies keep infant mortality high among culture organisations. I do not have the facts to dispute this. But what augurs well for the arts, I think, is the calibre and effectiveness of those that survive. In this respect, Madras is singularly fortunate and richly deserves its reputation as an active and flourishing centre of culture.

Today, there are many such organisations in the city – most of them private and some State subsidised – which are doing more for the survival of classical art than perhaps all the Akademis put together. (At least they do not waste any money promoting mediocrities.) The economics of conducting an organisation of this nature was explained to me the other day by an official of the Narada Gana Sabha – one of the smaller but very ably managed groups in the city. On the membership rolls (in many cases popular enthusiasm is such that these are fast becoming unwieldy), you have a few hundred or more art enthusiasts, from whom, annually, a nominal fee is collected. A large number of first-class performances- including music concerts, dances and dramas – are staged each year. Non-members can also attend by buying a ticket, which seldom costs more than Rs. 10 or Rs. 15. All the money is utilised for getting top notch artistes in the future, as well as for the very commendable purpose of providing a stage and audience for promising newcomers. In the long turn, entertainment of a very high order is made available to a large number of people at a price they can afford. Can the cause of “popularising culture” be more effectively served?

* * *

“While on this topic, I am constrained to observe that the crop of arangetram-s in recent times makes one suspect that an enthusiasm for culture (even in Madras) can sometimes be grossly misplaced. I remember the old days when Convent education was much admired and many a proud parent, under the mistaken notion that he is providing you with entertainment, would drag a self-conscious and fidgety child before you and make him recite, say “Jack and Jill”, with appropriate gestures to illustrate the final tragedy that befell this pair. Nowadays, Bharata Natyam or Kathakali seems to have taken the place of such impromptu recitations, and the scene, alas, has shifted from the drawing-room to the public stage.

When you are least inclined to be entertained, you receive an invitation to the arangetram of the daughter of a Government official or a company executive, and you can reject it only at the risk of spoiling an otherwise happy personal or business relationship. At these functions, normally graced by a VIP, all kinds of people are dragged on to the stage and smothered in huge garlands dripping with water, and ultimately one of them, his shirt half-drenched and strewn with rose petals, takes up his position at the mike, a long introductory speech follows, in which praise is indiscriminately heaped – on the VIP, the proud parents, the performer and the guru – in that order. Then the second – and what should really have been the first – part of the show begins.

It is a pity that many of these girls are no great credit to their gurus. More often, it is parental pride rather than any proficiency in the art that qualifies them for the limelight. But, of course, gurus have also to make a living, and I have no doubt that they, too, suffer in silence with that section of the audience made up of people who are in no way related to the performer. One’s only consolation is that at the end of the show, when that chaotic congratulatory atmosphere prevails in the hall, one can slip out of a side door, unnoticed, to go home and pray for the future of Art!