Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXXII No. 14, November 1-15, 2022

A legendary Madras writer-author and her work on a Madras legend

-- by Anantanarayanan Raman, anant@raman.id.au

I am unable to recall precisely. I must have been in senior class in the M. Ct. Muthiah Chettyar Boys’ High, Purasawalkam. But what I remember vividly are my regular push-bike trips to the then new District Central Library (presently the Devaneya-Paavanar Nulagam) in Mount Road. I first chanced on the book Doctor Rangachari by Rajam Krishnan there, published by Swadesamitran, Mount Road, Madras, in 1965. C(hetpet) P(attabhi-raman) Ramaswami Aiyer has written the foreword for Rajam Krishnan’s Doctor Rangachari. Popular obstetrician – gynaecologist of yester-year Madras, Arcot Lakshmanaswami Mudaliar has reminisced briefly on his association with Rangachari. Kamalamma, wife of Dr. Rangachari, has provided a short note of her life with him. In her note, Kamalamma says: ‘In principle, I lived with him for 31 years. If one were to calculate accurately, I would have lived with him for hardly 31 days. All of his time, he committed to the sick and suffering. I am fully happy with that; I have nothing to complain.’

In the next two decades, I must have read Doctor Rangachari at least 20 times; this is an honest statement. This book means so much to me. Every time I read this book, I asked myself, in absolute awe, whether a human could have lived so humanely! He must have; otherwise, Rajam would not have portrayed him and his life so warmly, elegantly, and touchingly.

Rajam Krishnan (date unknown) Source: pustaka.co.in

Rajam Krishnan (date unknown) Source: pustaka.co.inFirst about Rajam. Rajam was born in Musiri in the 1920s. She had little formal education,yet her writing started when she was in her 20s. A powerful spark seems to have ignited her young intellect to write, reminding me of Bharati’s brilliantly shining intellect. Tamil-literary world recognizes her for her critically researched social novels on people, who are customarily ignored in creative writings. For example, Rajam wrote about the less-recognised humans; importantly, about female labourers. Her life-time work includes the publication of 40 novels, 20 plays, two biographies, in addition to several short stories. She translated Malayalam short stories in Tamil. Contemporary Indian women activists, Susie Tharu (English and Foreign Languages University, Hyderabad) and K. Lalita (Osmania University, Hyderabad) in their Women’s Writing in India applaud Rajam saying ‘she set a new trend in Tamil literature’ by particularly referring to Rajam’s extensive and intensive research made to shed light on the abysmal social conditions and women of the then Tamil Nadu and India, while setting the backdrop in her writings. Tharu and Lalita acknowledge Rajam as a revolutionary woman of the Tamizh country. Padma Narayanan and Prema Seetharam (both authors and translators) have expressively spoken on Rajam’s life and works. However, I felt disturbed on reading on Wikipedia that ‘Rajam was left poor and destitute in her later years and had to be admitted to an old-age home. She died in the old-age home in Tambaram on 20 October 2014.

In the present Tamil Nadu, the term aalumai, which – to me – means a ‘dignified, commanding personality’, is used widely. I like MSik because it means positivity, promise, and potential, laced by self-confidence and capability. Rajam amazes me as the sinew of the social fabric of Madras, who made clarion calls for the causes of destitute and disparate women, although, sadly, during her old age she was a victim of disregard and neglect. Rajam stands a cut above the rest of her contemporaries as a dazzling aalumai of the 20th-21st Century Madras. She impresses me as a majestically grand woman of Madras, who proved beyond any doubt, that intelligence and wisdom have no bearing on formal education.

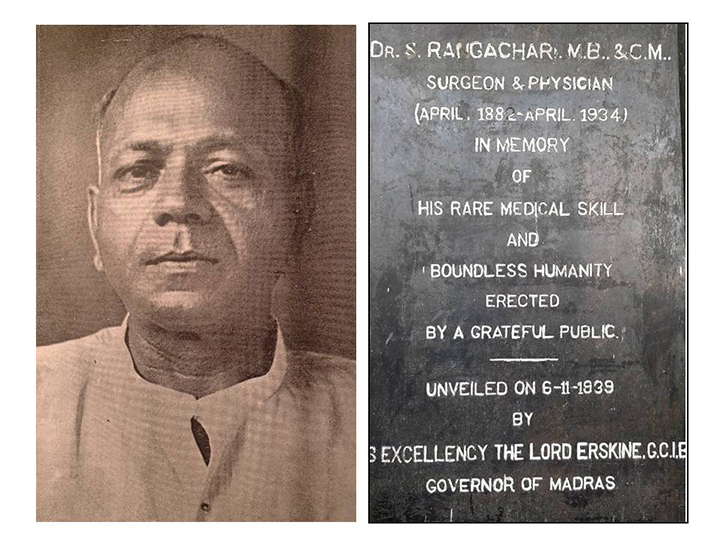

Left: Portrait of S.R. in Rajam Krishnana’s Doctor Rangachari (1965). Right. Stone plaque on the pedestal of S.R.’s statue at the main entrance of Madras General Hospital.

Left: Portrait of S.R. in Rajam Krishnana’s Doctor Rangachari (1965). Right. Stone plaque on the pedestal of S.R.’s statue at the main entrance of Madras General Hospital.Briefly about the hero of her biographical work: Sarukkai (Srinivasa) Rangachari (1882-1934, hereafter, ‘S.R.’). As a medical practitioner in Madras from 1906, S.R.’s days started at 4 in the morning. From 1906 till his death on 24 April 1934, his work days were rigorous, spreading up to 18 hours a day. He performed surgeries until around 11 a.m. each day in his clinic Kensington on Poonamalee High Road. He saw out-patents later, followed by house visits. On many a day, he ate his lunch in a hurry in his Rolls Royce Phantom I. With the break-out of typhoid in Madras in 1934, Rangachari pushed himself to work longer hours to reach out to the sick. The Typhus bacillus did not spare S.R. He succumbed to typhoid at the peak of his popularity as (people’s doctor). The Madras public honoured this ‘flying’ doctor – who criss-crossed India treating the sick travelling in his 3-seater de Havilland DH 80-A Puss Moth, a high-wing monoplane – by erecting a life-size statue, unveiled by John F.A. Erskine, Governor of Madras (1934-1940), on 6 November 1939. This statue stands near the gate close to the Casualty Department of the Madras General Hospital with the words ‘In memory of his rare medical skill and boundless humanity’ inscribed on the pedestal (see picture below).

Rajam presents S.R.’s life and work in a conversational mode. Her prose is enchantingly captivating because of this style of presentation. I provide here three examples to illustrate her unique and mind-capturing style.

The first two examples relate to the young S.R. and how some of his early-life experiences shaped him in choosing medicine as his career in spite of odds. S.R., a student in the F.A. class at the Madras Christian College, then in Armenian Street, George Town, meets a younger school-going boy by name T(ôdûr) M(adabûsi) Rangachari (‘T.M.’) in Sarukkai village, Paapanasam, Thanjavur (pages 11-13). A brief conversation evolves between the two Rangachari-s. S.R. asks T.M. ‘what a person cannot afford to lose?’ expecting ‘time’ as the answer. But T.M. surprises S.R. answering ‘life’. Biographer Rajam embeds a comment here: “On being careless, ‘life’ cannot be re-gained as well. The element of permanent loss also fits well with ‘time’. Which of these two – time or life – is more critical?

Once ‘life’ leaves a body, it never returns.” Because the conversation turns into an argument between S.R. and T.M., the older S.R. mumbles to himself that T.M. speaks out of youthful ignorance. However, Rajam inserts rousing remarks supplanting this conversation for our benefit: ‘Life and living are the greatest; no human can re-gain life after losing it. Death conquers life through ageing and disease’. How could a biographer be more picturesque with words for the transformation of (or ‘enlightenment in’) a young mind to choose the medical profession as an effort to save lives? A brilliantly imaginative and smart introduction! Second example: S.R. clears the F.A. class with high grades. His father Raja Srinivasa Iyengar, a construction engineer with the Government of Madras prefers that S.R. joins either B.A. programme to enter educational service or B.E. programme to train as an engineer, much like himself. S.R.’s uncle advises him to study ‘law’. ‘None of these; I am going to study medicine and become a doctor’ replies S.R. to his father and uncle. Raja Srinivasa Iyengar and S.R.’s uncle are shocked and dismayed: they find it hard to accept a boy born in an orthodox Sri Vaishnavaite family wanting to study medicine that will call for dissection and exploration of cadavers! ‘Pus and blood, pain and sorrow are the permanent companions of that profession, right?’, they both ask S.R. The elders in S.R.’s house find his retaliatory response grossly unacceptable. SR throws down the gauntlet: ‘In legal profession, truth is veiled on purpose; is that not a sin? My decision to pursue medicine is firm. No change.’, leaving them stupefied and aghast. S.R. joins the Madras Medical College to pursue M.B. & C.M. degree (Medicinae Baccalaureus et Chirurgiae Magister that literally translates into ‘Bachelor of Medicine & Master of Surgery’, a predecessor of modern M.B.B.S. programme.) Rajam embeds her remark here: ‘Can a farmer get into the field to grow crops shunning slush and dirt? Can the farmer loathe the unpleasant smell of rotting manure in the field? When one is immersed in the thought that his/her labour is going to satiate hunger of many, and that thought makes that person proud as he/she moves towards his/her goal. Where is the space for individual feelings?’ The young S.R. enters M.M.C. to understand the structure of human body, so that he could treat human illnesses and also with an aim that he will do his best to relieve pain of humans.

The third example pertains to S.R. as an established practitioner in Madras, working at Kensington, Poonamalee Road (note: not Poonamalee ‘High’ Road). In p. 281, Rajam narrates the following: A male load-cart puller with exhausted feet that have been reduced, literally to nothing, in spite of the jute-sack material wrapping his feet, comes to S.R. with a fractured arm after hit by a motor car near Kensington. S.R. treats him and bandages his fractured arm. The cart-puller gets well in the next few weeks and returns to see the doctor. He pulls out a few scrunched small currency notes and some coins saved by him over time to pay the doctor. ‘Your fees, doctor,’ says the cart-puller. ‘My fees? Do you know what you should give me?’ asks S.R. The cart-puller wonders whether the doctor was going to ask him to mend the garden in Kensington in lieu of the fee. The doctor takes him to his Rolls Royce parked at the front and honks its rubber horn, which obliges with a resounding blare. ‘Did you hear this sound?’ S.R. asks. ‘Whenever you hear such a sound while being on the road, you should allow a safe space for the sounding vehicle to pass around you. Will you promise me to do that in future? That promise is the fee.’ In the next few minutes the angelic motorcar, Rolls Royce Phantom I, swiftly disappears on Poonamalee Road, leaving the cart-puller in surprise and amazement.

S.R.’s Puss Moth carried him to suffering people at far off places, not connected by either roads or rails. His Puss Moth reached him on time to women experiencing complicated child birth, because of problems such as fœtal distress, perinatal asphyxia, and uterine rupture, that were extremely serious in the 1920s. In p.280, Rajam speaks of his rushing to the Lady Pentland Women & Children Hospital in Kaanadukathan (presently Karaikudi District) because of a call from a woman doctor in that hospital. His Puss Moth transported him to Travancore (presently Thiruvananthapuram) to attend to the health needs of the prince; it also flew him to Kumbakonam to attend to the emergency of a milkmaid in an advanced stage of pregnancy, who was knocked by a cow during milking.

I stop this narration here. Too many moving anecdotes and touching narratives, charmingly strung together using simple, yet powerful words. I have never felt tired of reading Doctor Rangachari again and again. As I write this note, I have started reading this inspiring book again. Every medical student of Tamil Nadu – why Tamil Nadu only, the whole of India – should read this book to feel the pain experienced by humans and the magic S.R. created! So remarkably Rajam portrays S.R.’s life and work! As I said earlier, I am finding it hard to believe that a person could have lived so magnificently, magnanimously, and humanely! He must have; otherwise, the then general public of Madras would not have voluntarily subscribed to erect a memorial for this true and great human! S.R. acquired loads of money, but none through demand. Everything was given to him voluntarily, whether small change from the less fortunate or large notes from the privileged.

Although born in an orthodox family, nowhere Rajam indicates of S.R.’s practice of his family traditions and theological beliefs. Maybe he held the faith. But that is not apparent. To me, he lived as a karma yogi, which is also reinforced in Kamalamma’s note.

Comments