Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXXII No. 12, October 1-15, 2022

On the quarter-millennial anniversary of the Madras General Hospital – II

-- by Ramya Raman, Anantanarayanan Raman

(Continued from last fortnight)

The action of the Jury caused some dissatisfaction among the British community, since the community considered that a case of criminal negligence had been made out. This is the first recorded medical forensic autopsy in India done in Madras in 1693. Notable is that this autopsy included submitting a formal report to higher authorities by Edward Bulkley, who functioned similar to a modern police (forensic) surgeon, in addition to his general duties.

Between 1693 and 1762

The MH, in the meantime, moved at least to six different locations, and in later times out of the Fort. It functioned in the Esplanade in 1753, Peddanaickenpetta in 1757 and, later, to the present location of the GH in Periamet.Unfortunately, no relics of the facilities that operated earlier exist today.

The General Hospital of the Presidency

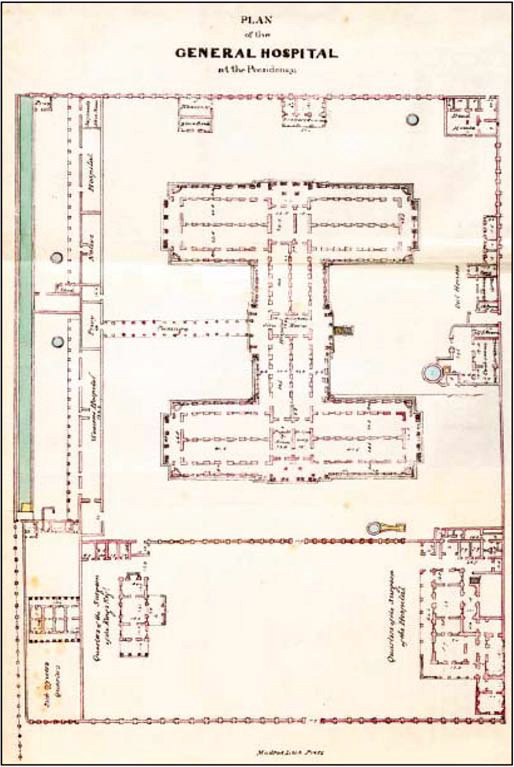

The reason for locating the MH at the Périamét site was because the previous location was considered unhygienic. The government at the Fort considered that a proper building was to be erected soon to accommodate 500 men and 30 officers. Patrick Ross, Chief Engineer, submitted a proposal at an estimated costing of 46,500 pagodas. John Sullivan, a young clerk in the Fort, offered a plan costing 42,000 pagodas. Sullivan’s proposal was accepted and a one-storey building came up and the new hospital building was completed and occupied in 1772. This hospital came to exist in its present location on Poonamalee High Road (presently Périamét and opposite to the Madras Central Rail Station), then referred as the Hog’s Hill. By the 1840s, this facility came to occupy a well-constructed (indicated as pukka) building with a terraced roof and brick floors raised from the ground by a foot (c. 30 cm). It consisted of three blocks, two of them running parallel and interconnected by a third – appearing similar to the letter of alphabet ‘H’ in aerial view – with the main entrance located on the eastern side. The connecting median building included the commissariat stores. Twelve wards existed, each ward intended to accommodate 16 patients: thus 192 inpatients at one time. The facility was, however, amenable to accommodate more patients during emergencies (Fig. 2).

FIG 2. Floor plan of the General Hospital of the Madras Presidency.

FIG 2. Floor plan of the General Hospital of the Madras Presidency.The GH expanded further in 1859; exclusive wards for women and children were added in 1897. It became a civil hospital from being an exclusive MH in 1899. By 1909, there were 500 beds, and about 450 outpatients were treated every day. The GH was intended to treat persons serving the government and their families, and the civilian population. The sick were separated as Europeans, Eurasians (Indo-Britons, Anglo-Indians), Hindus, and Muslims (indicated as Muhammadans). The logic behind this artificial separation was that the British were displaying cultural sensitivity, which, of course, did not achieve that purpose. Rules and procedures were discriminatory. Rule 520 of GH states: ‘Bedding and clothing of the European patients shall be changed twice a week and of the native patients once a week; oftener if necessary.’ Such differences concretised the separation between the British and locals reflecting the British attitude of considering the Indians inferior.

Medals honouring a private medical practitioner Joseph William Turner Johnstone in Madras and the GH Surgeon Ambrose Blacklock exist today with the Madras Medical College (MMC). Both Johnstone and Blacklock medals are considered prestigious by MMC graduates. Many medical officers attached to the GH and holding conjoint academic positions at MMC, before 1947 sparkle in the pages of Madras’s medical history.

Donovanosis, also known as granuloma inguinale, was first recognised and described in Madras in 1881, as serpiginous ulcer by Kenneth MacLeod who joined the Indian Medical Service in Madras and later became the professor of surgery in Calcutta. The causal agent of granuloma inguinale was discovered by Charles Donovan. Donovan described the intracellular bodies in 1905, which bear his name. The so called ‘Donovan bodies’ were found in wound exudates from an oral lesion of a ward boy of the GH. Donovan thought that the causal agents were Protozoa. Only in 1943, the ‘Donovan bodies’ were determined as Klebsiella granulomatis (Enterobacteriales: Enterobacteriaceae). The aetiology of donovanosis and its venereal nature were elucidated subsequently. Donovan’s discovery of the visceral leishmaniasis-inducing protozoan was made when he was the professor of medicine at MMC, which was the teaching wing of the GH, and conjointly superintending the Royapettah Hospital. Charles Donovan is one name, which Madras takes immense pride to associate with, because of his outstanding contribution to medical science. Ramakrishna Venkata Rajam, the first Indian Dean of the GH–MMC complex eloquently waxes on his teacher-mentor Donovan in his WHO report. The fascination to indulge seriously in medical research seems to have been strongly instilled into Rajam by Donovan. The Donovan legacy sustained by the ‘R.V. Rajam-P.N. Rangaiah-C.N. Sowmini’ academic dynasty is a landmark phase in Madras’s medical science, which remains unmatched even today.

William Niblock was a contemporary of Charles Donovan, but is less known even in Madras’s medical circles. Thorough in his methods, he was a skilful and expert surgeon, with an extraordinary knack of instilling total trust and confidence in his patients. Among his several contributions to medicine in Madras, Niblock is remembered for the first and successful gastrojejunostomy he performed in the GH on 2 March 1905 as a treatment for gastric outlet obstruction caused by peptic ulcer. Niblock was the first in India (and perhaps in the world) to scientifically indicate the relationship between chewing of tobacco and oral cancer, studying the illness in 60 patients from the GH. His study using 60 patients reinforces his commitment to scientific accuracy. The book Around the world via India – A medical tour refers to Niblock’s surgical skills in treating oral cancers, testicular filariasis, and stones in the liver, gall bladder and kidney. Records exist that Niblock also treated patients suffering glaucoma, although the Government Ophthalmic Hospital (previously the Madras Eye Infirmary) in Egmore was functional then.

Started as a military facility, the GH today has grown by leaps and bounds serving the people of Madras and India. With several well-equipped specialty departments, this hospital is an asset to health management in India. After India’s Independence, the GH was decorated by physicians such as Rathnavél Subramaniam, Alagappan Annamalai, Krishna Varadachari Thiruvengadam, and Sam Moses, and surgeons such as C.S. Sadasivan, Solomon Victor and Balasubramanian Ramamurthi, who made great strides in ensuring the better health of the Madras public.

(Concluded)