Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXXII No. 19, January 16-31, 2023

Public Hospitals in Madras and the people associated with it – Part 1

-- by Anantanarayanan Raman, anant@raman.id.au

In this article, we refer to the public hospital facilities of Madras, viz. the Lock and Naval Hospitals, the Native Infirmary, Lunatic Asylum, Eye Infirmary, Maternity Hospital (Egmore), and the Queen Victoria Hospital for Caste and Gosha Women, some of which are operational today. We also include brief notes on a few of the pioneering Men and Women, who contributed to the development of these facilities.

The Lock Hospital

The mid-19th century army health statistics of Madras and India indicate that morbidity rates were especially high (nearly 30 per cent) among soldiers suffering from sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). One Assistant Surgeon – John Clark – indicates that more cases of STD occurred in one army regiment in India than in the whole of the Caribbean island nations. The Madras Army surgeons contended that syphilis and gonorrhoea were modestly different manifestations of the same disease.

The government in Bengal made an effort to combat STD by establishing ‘lock’ hospitals in 1807. Lock hospitals were dedicated clinics for those suffering from venereal diseases. The earliest one was the London Lock Hospital, established in 1747. Traditionally the term ‘lock’ referred to the ‘rags’ used by patients of leprosy to cover themselves. Therefore, the lock hospitals implied hospitals treating patients of leprosy. However, these hospitals came to be better known for patients suffering from venereal diseases in later times.

Following Bengal, the Madras Army established lock hospitals in major army stations in the Madras Presidency. By 1810, about 3,500 women were coercively and punitively treated in lock hospitals in Madras presidency. Funding for these hospitals was calculated by a combination of an allocated amount for facilities and a per-capita fee levied on every treated person. William Bentinck (1774–1839), Governor of Madras (1803–07) and the Governor-General in Calcutta (1828–34) was, however, not happy with the coerciveness enforced in this context. To Bentinck, the lock hospitals were a short-term solution; they did nothing for the involved female, but only checked the spread of infection among the troops, that too, indirectly. Consequently, the lock hospitals were shut down in Madras Presidency. However, the story does not end there. There was a substantial increase in the rate of incidence of venereal diseases by 1835, implicated as due to the abolition of lock hospitals. Caught between what were unacceptable levels of venereal infection and London’s disapproval of continuation of lock hospitals, some Madras Army officers, colluding with a few local surgeons, planned makeshift arrangements. Voluntary lock hospitals and dispensaries re-emerged, where free treatment, shelter and food were offered to ‘attract’ destitute women. The lock hospitals reappeared formally in the 1850s with the establishment of one by the Madras Government in Cannanore (Kannur, a part of the Madras Presidency until 1956; presently a district of the State of Kerala) in 1849. Lock hospitals functioned in the Madras Presidency until the 1890s. About this time, the Government in Madras planned to employ women nurses at these facilities as an improvement measure, which was rejected by the Government of India. Surgeon General George Smith in his consolidated report on the lock hospitals in India, published in 1878, indicates that one lock hospital existed in Madras town in 1877. This report describes the conditions and staffing in and expenditure of lock hospitals in Madras presidency. This report also supplies comprehensive statistics of various venereal diseases, especially those of syphilis and gonorrhoea in the decade from 1867 to 1877.

The Naval Hospital

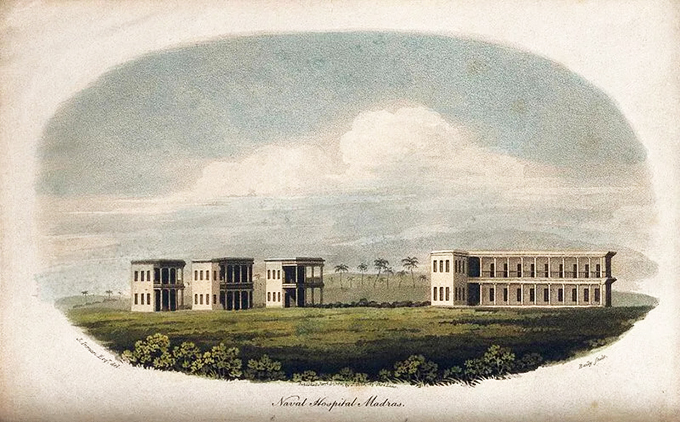

The Naval Hospital, Madras. Aquatint by J Baily of the Naval Hospital, Egmore.

The Naval Hospital, Madras. Aquatint by J Baily of the Naval Hospital, Egmore.An exclusive hospital was built in Madras (commencement 1784; completion 1808) for sick seamen travelling on British frigates to countries governed by Britain. Until 1808, the Military Hospital (MH) operating within the Fort St George serviced the sick seamen as well. The MH included two independently managed wings: a ‘garrison hospital’ on the western side of the building and a ‘naval hospital’ on the eastern side.

After establishment, from 1808, the Madras Naval Hospital (MNH) treated European and Eurasian (Anglo-Indian) civilians. For a glimpse of the structure of the MNH and the common diseases that were treated therein, see Charles Curtis (Curtis C. An account of the diseases of India, as they appeared in the English fleet, and in the Naval Hospital at Madras, in 1782 and 1783; with observations on ulcers, and the hospital sores of that country) who also provides the medical history in Madras until 1808. The MNH, located in an exclusive building at the dedicated site, was closed in 1831 and the building was converted to a gun- carriage factory. The road that housed the Naval Hospital was known as the ‘Naval Hospital Road’. This road is opposite to the Government College of Fine Arts on Poonamalee High Road. The premises are presently used as the medical-store depot of the Government of Tamil Nadu.

The Madras Native Infirmary

Government Ophthalmic Hospital in Marshalls Road (1886). (From MM Archives.)

The Madras Native Infirmary (MNI) was established for the sole purpose of providing medical help to the native poor of Madras in 1799. The MNI was attached to the Monégar Choultry (MC), which was the English corruption of Maniyakkãrar Çattiram (Tamil). MC was operational from 1784 as a centre to disburse kanjí (sour-rice porridge, gruel) free to the famine-stricken poor of Madras. Assistant Surgeon John Underwood suggested setting up an hospital at MC in 1797, which evolved as the MNI in 1799. The government made available Rs. 54,358 to the newly established MNI, treating it as a joint charity in 1809. The MNI grew into a ‘hospital’ shortly after, with the construction of a few pent-roofed brick sheds. This facility included exclusive male and female wards, separated by a high wall to accommodate 140–150 lying-in patients at a time. The wards were well aerated with doors and windows further to ventilators in the roof. An ‘excellent’ surgery was done within, in addition to the quarters for an apothecary, and a dispensary to issue medications to outpatients. John Underwood was the first superintendent. This hospital was managed by a team consisting of Merchant William Webb and Aldermen Nathaniel Kindersley, Charles Baker and John de Fries. In the first decade of the 19th century this hospital was managed by the MC administration.

This facility included seven separate ‘cells’ for the mentally ill, both men and women. The most critical inclusion at the MNI precinct was the Leper Hospital, which was in a building separated by a 12 feet high wall. The Leper Hospital and other facilities within the MNI precincts were divided by a road that passed by (today, the Ennore High Road) to avoid interactions among inmates of the two hospitals.

Remittent and eruptive fevers, cholera, diarrhoea, atrophia, phlogosis and ulcers were few of the major illnesses treated. The MNI grew first into the Royapuram Medical School in 1933, and as the Stanley Medical College and Hospital in 1938, named so after George Frederick Stanley, Governor of Madras during 1929–34. The new ‘Licenced Medical Practitioner’ (LMP) diploma offered at the Stanley Medical College and Hospital was an innovation in Madras’s health-management effort, especially after World War I. The government under the premiership of Panangati Ramanarayaningar (a.k.a. the Rajah of Panagal) utilized the LMP qualified personnel in the Subsidized Rural Medical Relief Scheme (SRMRS), a novel health project launched in 1924, which operated with the objectives of bringing medical relief to rural people and encouraging the trained medical practitioners to settle in remote and rural areas.

(To be continued next fortnight)