Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXXII No. 8, August 1-15, 2022

When Chess was played in Olde Madras

-- by Sriram V

The 44th Chess Olympiad is all the buzz in the city and by the time this issue reaches your hands, we are sure that the tournaments will be moving towards the grand finale. True, the Russian aggression in Ukraine has been the reason for this sports-meet to move to Chennai but then none can argue that our city is a chess capital. In fact, Madras Musings, as early as in its February 16 issue in 2001, had declared it to be so. It must however not be forgotten that what we are seeing today is a culmination of several years of effort and passion for the game.

It is accepted that modern chess as we know it has its origins in an ancient Indian game known as chaturanga. In recent times, excavations at Keeladi seem to push the timeline further back, with the emergence of objects that are similar to chess pieces. The Sanskrit word chaturanga is essentially descriptive of the traditional Indian army, with its four (chatura) units (anga) – foot soldiers, cavalry, chariots and elephants. There are references in Sanskrit literature from at least the sixth century to chaturanga being played. However, modern chess seems to have come to India via the Europeans.

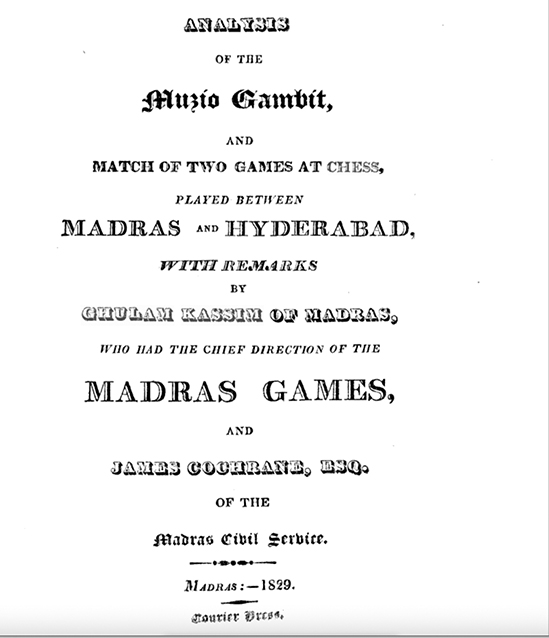

It is interesting to see that Madras or Chennai, was in the forefront of Indians taking to the game. As early as in 1829, a monograph appeared on two matches played between Madras and Hyderabad. The games were played via correspondence and lasted several months. Shah Sahib was the player from Hyderabad and Madras was represented by Ghulam Kassim about both of whom nothing much is known. The latter is credited to having ‘had the chief direction of the games’ in Madras. James Cochrane of the Madras Civil Services seems to have been a fellow chess afficionado and the two together brought out what was titled as the Muzio Gambit and Match of Two Games at Chess Played Between Madras and Hyderabad, published by the Courier Press, Madras. A full download of the document is available at archive.org. Unfortunately for someone with merely passing interest in chess it holds little of interest beyond a whole series of positions. The imagination however boggles at how the games must have been played by correspondence, with the two chess sets in the two respective locations remaining standing for months on end. Not surprisingly, a note in page 48 of the monograph says the person playing at the Hyderabad end died at the end of the 17th move in the first game and the 16th in the second. A monograph titled 19th century Chess by Bill Wall in archive.org notes that on the death of Shah Sahib, his junior Row Sahib, a ‘weaker player’ took over in Hyderabad and so we know a little bit more about this contest. The same monograph also records the year of death of Ghulam Kassim as 1844. It is not clear if this information is taken from Wikipedia, which carries the same date with no reference cited for it.

What is for certain is that Ghulam Kassim’s monograph became a widely quoted text through the 19th century and in 1880 we find that the author is being lauded as “a distinguished writer” on chess (The Saturday Review of Politics, Literature and Science, Mar 20, 1880, p 371).

In what may truly be a hallmark of everlasting fame, Kassim made it to fiction as well. Captain Hugh A Kennedy was a contemporary in Madras. Born in Madras in 1809, he went on to become a captain in the British army and post retirement lived in Bath, England from where he established his reputation as a leading chess player. He founded the Brighton Chess Club as well. Known to be a bit of a gossip, he took to writing on chess and frequently contributed to magazines in England. In the process he created the character of Lieutenant Augustus Fitzsnob, and compiled his fictional reminiscences which were published as part of Kennedy’s Waifs and Strays, Chiefly from the Chess Board (L. Booth, Regent Street, London, 1862). The account itself opens with a reference to W.M. Thackeray’s Book of Snobs and was clearly inspired by it. As per the reminiscences, Fitzsnob claims to have been present when Ghulam Kassim played his match against Hyderabad.

The name Fitzsnob and the doffing of the hat to Thackeray ought to have been dead giveaways but that was not so. Readers, especially the Americans it would seem, took Fitzsnob seriously. When Kennedy followed it up with a story of Fitzsnob being present at a game between Napoleon Bonaparte and Count Bertrand in St. Helena’s in 1820, it gained traction, and by 1857, the American Chess Monthly carried details, attributing the moves as given in Waifs and Strays to Napoleon himself. It was only in 1900 that the British Chess Magazine (Vol. 20, page 54) disproved the whole story and remarked on how people were mistaking an “adornment of a tale for a historic fact.” And just in case people then began to believe that H.A. Kennedy was himself present at the so-called match at St. Helena’s, it clarified that the Captain could have been only 11 years old when it was played! By the time this article appeared, Kennedy was long dead, he having passed on in 1878. Thankfully for us, Ghulam Kassim is an incontrovertible fact.

Surprisingly, there is no mention of chess in the city in H.D. Love’s Vestiges of Old Madras, though he does list several other games. As it records the history of the city from 1639 to 1800 and as Ghulam Kassim’s game was in 1828/1829 it is possible to surmise that Indians took to playing chess in the first two decades of the 19th century. Interestingly, it would seem that the mofussil, or what was Madras Presidency had its share of star players among Indians. Allen’s Indian Mail of May 12, 1860, carries details of an Indian of Bellary who was exhibiting extraordinary feats of memory. A reading reveals him to be an ashtavadhani – one who can perform eight tasks at the same time. Thus he played two games of chess, without looking at the boards (!!!) even as he played a game of cards, recited some verses and did a whole host of other things. After three hours of all these activities, he remained silent for an hour and then was able to describe every move made on the chess board, in correct order. Among those who marvelled at his feat was Lord Elphinstone who gave him a testimonial.

Similarly, the Chess Player’s Chronicle, carries a letter from a Mr. JIM of Negapatam dated April 14, 1847 which praises the skills of Vencut Agar, a Tanjore Brahmin. JIM (whoever he was) and Vencut Agar had played the game and the former considers the latter would have ranked “as a strong player in any country. He is of course ignorant of the Book openings, but he is a very cautious player and his patience and resource in situations of difficulty always bring him through safely. I have some of his games recorded except the first we ever played together, which I had the fortune to win by a coup de main. Since then, out of some twenty games we have contested I have only been able to win one other and draw one.” The note ends with JIM hoping that he will be able to soon send some details of the games he played with this “Tamil Phillidor.”

All of this makes for most interesting reading and we realise that Madras was seeing some isolated leading lights flickering here and there in chess in the 19th century. It must have appealed hugely to the Indian mind for it could be played seated, challenged the intellect and lasted for days on end. It is clear that people like Ghulam Kassim, the man from Bellary and Vencut Agar were all forerunners of thousands who would take to the game in the 20th century.

(To be concluded next fortnight)